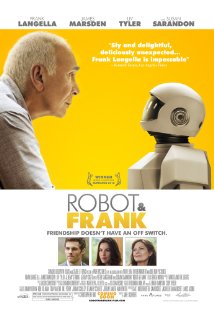

Befitting a movie about a man losing his memory, Frank Langella's character in Robot & Frank is also named Frank to keep things simple. And true to the title, his companion is a robot, assigned to care for the old man. Afflicted with not-explicitly-stated-but-obviously Alzheimer's disease, Frank gradually reveals himself to be a retired thief, still capable of pulling off small grabs and even intricate break-ins but less able to remember what it is he wants to steal, or why it is an awful idea in the first place. Initially resistant to the idea of having his diet and activity controlled by an eerily pleasant, vaguely humanoid being, Frank soon relents when he learns that he can convince his caretaker to assist in burglaries.

That Frank's children (James Marsden and Liv Tyler) did not think to program the robot to prevent their once-incarcerated father from committing further crimes speak to how little they think the addled man can do, an unwitting admission of their perfunctory sense of filial duty. As Frank slowly bonds with his personal trainer and eventual accomplice, the robot becomes a complex repository for the emotionally (and, often, physically) absent parent to both vent his frustration with his kids and to vicariously attempt to make amends with them. So effortlessly does Langella invest these feelings into the emotional void of his "co-star" that Robot & Frank works best when its thin commitment to a narrative evaporates and lets the actor simply inhabit his odd role.

Only for a brief window, in fact, does the storyline truly mesh with the film's emotional content in such a way that neither is sacrificed for the sake of the other. This synergy owes to the emotional investment Langella gives Frank's lingering need to steal, possibly the only thing that makes him feel like himself as so much slips away to dementia. Occasionally, he confides in his robot pal how he wishes he could have planned jobs with his children, his inability to share his greatest happiness with his greatest loves a regret he cannot forget.

As for the "heists" themselves, however, these setpieces serve only to insert story into a film working just fine with its less propulsive, more insular conflicts. Whether the initial break-in of a library on the cusp of conversion into a social museum for hipsters or the spiteful plan to steal from the hipster-in-chief (Jeremy Strong) in charge of this travesty of art and knowledge, Frank's heists do not follow through on the sense of irony and buried affection in the preparation the old thief puts into these jobs. When training the robot to use its super-human mechanical abilities for crime or reinvigorating his own brain with a focus and determination it has not had in years, Frank injects deadpan humor and life into the picture. But the big shows lack the lackadaisical charm and subtle insights of the rehearsals, and they gradually lead to an overactive story that reaches for big emotions and shameless plays on Frank's mental condition (which affects short- and long-term memory at the convenience of the plot), culminating in a twist so offensive in its casual manipulation of mental illness that the already eroding goodwill I had for the film evaporated.

Nevertheless,Nevertheless, Robot & Frank often manages to be quirky without all the tedium that term now entails. Langella's mixture of irascibility and regret gives the moments with Frank's children extra bite, even tragedy. Tyler's Madison rails at the notion of her brother pawning off their dad on a robot, but she decries Hunter from the convenient safe zone of her constant world travel, something even Frank, who pushes his son away, directly notes. When she finally does shows up in a fit of Luddite self-righteousness, she interrupts her father's scheme and prompts Frank to go to darkly amusing lengths to alienate his daughter and get his partner in crime reactivated. Marsden, on the other hand, gets to share some of Langella's pathos as the son who, despite rarely seeing his father as a child, tries his hardest to care for his dad, sacrificing his free time to drive hours at a time to tend to a man who does not want his help. And true to Frank's complex, mordantly funny/painful views of his children, the best moment of the busy climax concerns the old man playing on his son's strained affections one last time, using Hunter's desire for reciprocated acceptance to make the poor man an accessory. That Langella can play this almost sadistic exploitation for laughs without diving into caustic irony is a testament to the easy humanity and puckishness of his performance. That the film relegates this moment to but one minor moment within a distracting, clumsy, caper story is a testament to its wasted potential.

That Frank's children (James Marsden and Liv Tyler) did not think to program the robot to prevent their once-incarcerated father from committing further crimes speak to how little they think the addled man can do, an unwitting admission of their perfunctory sense of filial duty. As Frank slowly bonds with his personal trainer and eventual accomplice, the robot becomes a complex repository for the emotionally (and, often, physically) absent parent to both vent his frustration with his kids and to vicariously attempt to make amends with them. So effortlessly does Langella invest these feelings into the emotional void of his "co-star" that Robot & Frank works best when its thin commitment to a narrative evaporates and lets the actor simply inhabit his odd role.

Only for a brief window, in fact, does the storyline truly mesh with the film's emotional content in such a way that neither is sacrificed for the sake of the other. This synergy owes to the emotional investment Langella gives Frank's lingering need to steal, possibly the only thing that makes him feel like himself as so much slips away to dementia. Occasionally, he confides in his robot pal how he wishes he could have planned jobs with his children, his inability to share his greatest happiness with his greatest loves a regret he cannot forget.

As for the "heists" themselves, however, these setpieces serve only to insert story into a film working just fine with its less propulsive, more insular conflicts. Whether the initial break-in of a library on the cusp of conversion into a social museum for hipsters or the spiteful plan to steal from the hipster-in-chief (Jeremy Strong) in charge of this travesty of art and knowledge, Frank's heists do not follow through on the sense of irony and buried affection in the preparation the old thief puts into these jobs. When training the robot to use its super-human mechanical abilities for crime or reinvigorating his own brain with a focus and determination it has not had in years, Frank injects deadpan humor and life into the picture. But the big shows lack the lackadaisical charm and subtle insights of the rehearsals, and they gradually lead to an overactive story that reaches for big emotions and shameless plays on Frank's mental condition (which affects short- and long-term memory at the convenience of the plot), culminating in a twist so offensive in its casual manipulation of mental illness that the already eroding goodwill I had for the film evaporated.

Nevertheless,Nevertheless, Robot & Frank often manages to be quirky without all the tedium that term now entails. Langella's mixture of irascibility and regret gives the moments with Frank's children extra bite, even tragedy. Tyler's Madison rails at the notion of her brother pawning off their dad on a robot, but she decries Hunter from the convenient safe zone of her constant world travel, something even Frank, who pushes his son away, directly notes. When she finally does shows up in a fit of Luddite self-righteousness, she interrupts her father's scheme and prompts Frank to go to darkly amusing lengths to alienate his daughter and get his partner in crime reactivated. Marsden, on the other hand, gets to share some of Langella's pathos as the son who, despite rarely seeing his father as a child, tries his hardest to care for his dad, sacrificing his free time to drive hours at a time to tend to a man who does not want his help. And true to Frank's complex, mordantly funny/painful views of his children, the best moment of the busy climax concerns the old man playing on his son's strained affections one last time, using Hunter's desire for reciprocated acceptance to make the poor man an accessory. That Langella can play this almost sadistic exploitation for laughs without diving into caustic irony is a testament to the easy humanity and puckishness of his performance. That the film relegates this moment to but one minor moment within a distracting, clumsy, caper story is a testament to its wasted potential.